Mindfulness Buffers the Impact of COVID-19 Outbreak Information on Sleep Duration

By Michelle Xue Zheng, Jingxian Yao and Jayanth Narayanan

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to mass quarantine of communities across the globe. Such initiatives can have a negative psychological impact causing stress, anger and confusion. As the situation evolves, monitoring news of daily cases reported is important as it prepares citizens to be aware of a possible outbreak in their community and to take necessary steps to mitigate their risk of infection. However, such news also causes anxiety which in turn may lead to sleep disturbance. In combination with isolation that comes from social distancing, people in these communities may experience poor mental health and other negative outcomes. Moreover, this resulting sleep disturbance may end up hampering their immune response that is so vital to fight diseases.

Mindfulness, defined as non-judgmental awareness of the present moment, has been shown to lead to positive outcomes in domains such as physical health, mental health and behavioural regulation. Mindfulness has also been shown to lead to improved sleep outcomes. As such, we sought to examine whether a mindfulness intervention would buffer the negative effects of exposure to daily news reports about the COVID-19 outbreak on sleep. To examine this question, we recruited volunteers in Wuhan, China, who were in the middle of the largest lockdown in human history to prevent the spread of the virus. We conducted a randomised control trial with two treatments over a ten-day period.

We recruited 97 adults from Wuhan for a study testing effective ways of managing crisis. Eligible participants were residents who were located in Wuhan during the lockdown starting from January 23, 2020 due to the coronavirus outbreak. The study was conducted for 12 days between February 20 and March 2, within a month of the lockdown. Participants were paid 100 RMB (approximately $15 USD) upon completing the study.

Participants completed a baseline assessment on February 20 that asked for their demographic information and trait mindfulness a day before the intervention began. We used a design where participants in the mindfulness intervention condition engaged in 10 minutes of mindfulness practice each morning and participants in the mind-wandering condition engaged in 10 minutes of mind-wandering practice for 10 consecutive days from February 21 to March 1. Each morning, participants in both conditions received a series of audio instructions for mindfulness or mind-wandering practice and completed a short survey about sleep quantity, sleep quality, and caffeine intake in the previous day. Participants in both conditions also completed a short evening survey that assessed their anxiety levels.

As all our participants were native Chinese speakers, we used audio instructions in Mandarin that were recorded by a professional mindfulness coach. The audio instructions have been used in previous research and were effective in inducing mindfulness and mind-wandering in Chinese populations. To ensure that the programmes for the two conditions were comparable, the structure and voice tone of the recording in the mind-wandering condition paralleled those of the mindfulness induction, with two minutes of instruction followed by eight minutes of practice. In the mindfulness condition, the audio instructed participants to be present focused, aware of what was happening, and accepting. Participants in the mind-wandering condition listened to instructions for unfocused attention, an induction that elicits baseline wakeful states and that is often used as a baseline condition in mindfulness research.

Each morning, after listening to the audio instructions, participants rated their momentary mindfulness on four items on a 7-point Likert scale (1=not at all to 7=completely). The four items were “I focused on the present’’ ‘‘I thought about anything I wanted”, “I let my mind wander freely”, and “I was mindful of the present moment”. Participants in the mindfulness condition reported high levels of mindfulness than those in the mind-wandering condition, indicating that our manipulation was successful. We also measured anxiety on a 7-point Likert scale every evening.

Consistent with sleep research, we controlled for variables that may influence sleep quantity, including sleep quality and daily caffeine intake. We measured sleep quality on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from 1(very bad) to 7(very good). We measured daily caffeine intake with the question, “Did you consume beverages that contained caffeine (e.g. Coke, coffee)?”. We controlled for these two variables in predicting sleep quantity.

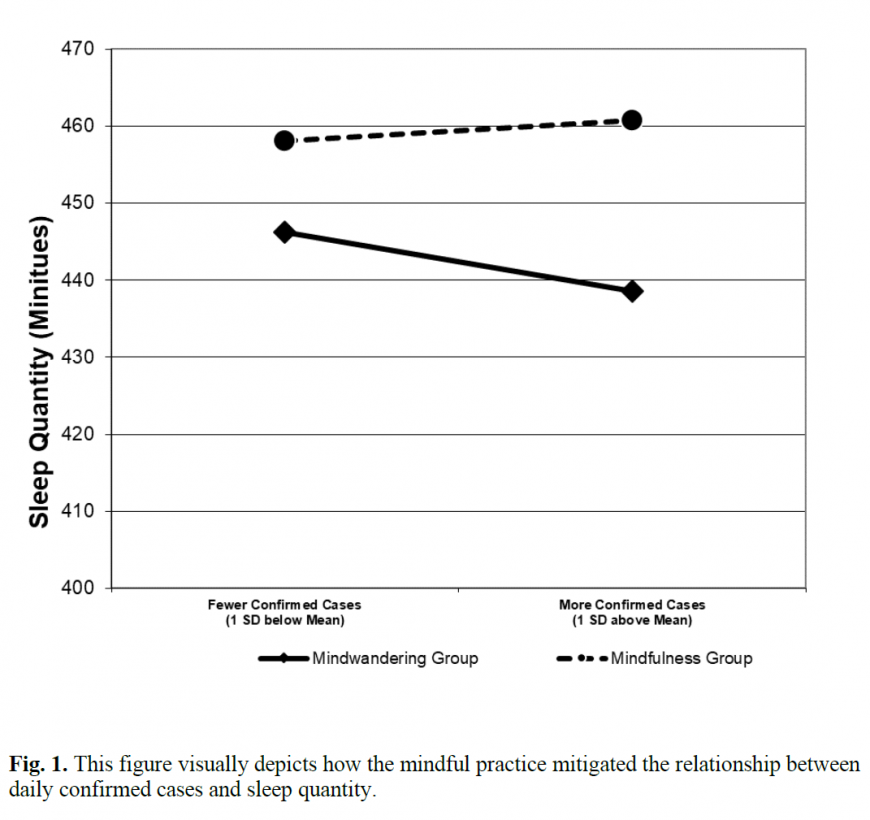

To test our research question, we examined whether mindfulness would help people cope with information about the outbreak in the city. In other words, we tested whether mindfulness intervention would mitigate the effect of number of daily confirmed cases on sleep quantity. Indeed, we found that mindfulness intervention positively predicted the random slope between daily confirmed cases and sleep quantity. To further probe the effect of mindfulness intervention, we plotted two separate slopes for the mindfulness treatment group and the mind-wandering treatment group. As shown in Figure 1, amongst people assigned to the mind-wandering treatment, the number of confirmed cases on a day was negatively associated with their sleep quantity on that day.

On average, the mind-wandering group lost 39 minutes of sleep with every thousand confirmed cases reported in the city. In contrast, amongst people assigned to the mindfulness intervention condition, their sleep quantity was unaffected by the number of confirmed cases. Furthermore, none of the other factors had the impact on sleep that the number of daily cases reported had.

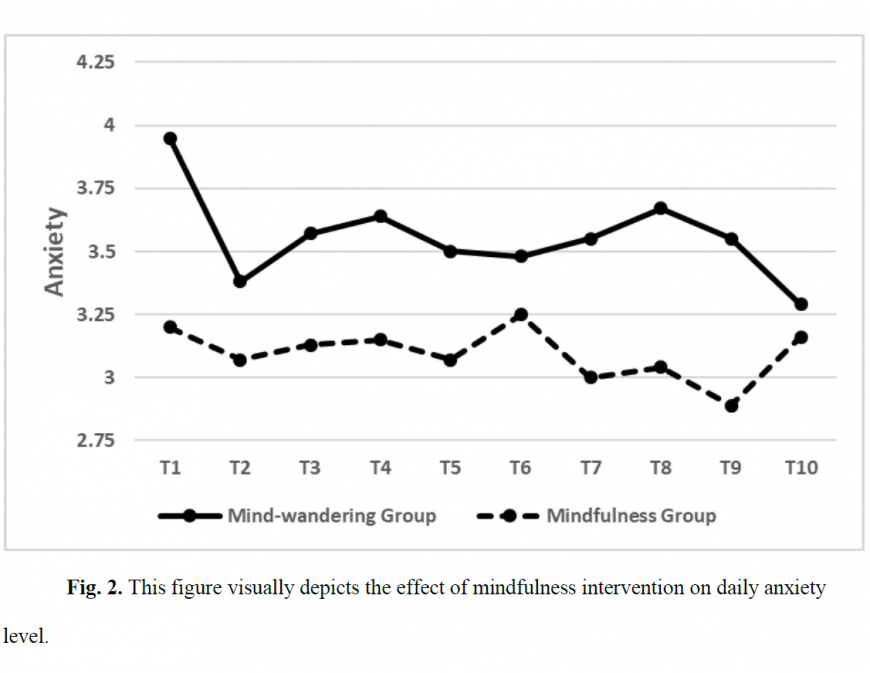

In addition, we examined whether a mindfulness intervention would lead to reducing anxiety level over 10 days. As indicated in Figure 2, we found that daily anxiety level of participants in mindfulness condition was lower compared to daily anxiety level of participants in mind-wandering condition.

We are in the midst of an unprecedented pandemic. As our ability to disseminate information about the pandemic periodically to the community has increased manifold. This comes with anxiety associated with the consumption of this information on an ongoing basis. Specifically, knowing that the virus is spreading in the community can have a negative impact on people. Given the boredom associated with social isolation and the lockdown many communities are facing, the tendency to ruminate over such information may affect sleep – the very antidote that can restore immunity to protect oneself if one were to catch the virus. Our study shows that a deliberate practice of mindfulness can help people increase the duration of sleep in the midst of the pandemic.

As a policy intervention, we suggest that administrators and citizen welfare groups organise mindfulness groups online where people can come together and engage in practice. This also perhaps has the benefit of creating a sense of belonging and mitigating the negative effects of social isolation that people may experience as humanity copes with this epidemic.

Michelle Xue Zheng is an Assistant Professor of Management at CEIBS. For more on her teaching and research interests, please visit her faculty profile here. Jingxian Yao is a PhD candidate at the National University of Singapore and Jayanth Narayanan is an Associate Professor at the National University of Singapore.